There are approximately 150 Mithraic sanctuaries in the Roman Empire (this number circulates in the recent literature, however nobody ever made an updated, complete list of sanctuaries since Vermaseren: a recent – however incomplete map – see here and here). Some of these sanctuaries were excavated in the early 19th century, therefore a detailed monograph was not possible to publish (still, sanctuaries of Ostia, Heddernheim or Sarmizegetusa were published with relatively well documented drawings). Most of the early excavated sanctuaries are published in form of short or long studies, but no detailed monographs are known for individual sites from the 19th century.

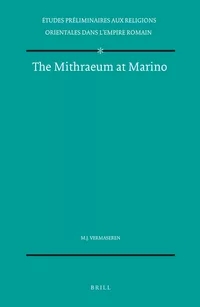

The 20th century produced several new excavations in the post-Cumontian period. During the lifetime of Vermaseren, several sanctuaries were published in form of a monograph. He himself published three sanctuaries in monographic form.

Here are some of the rare cases, where a Mithraeum was published in monographic form, the most detailed one – which can serve as prototype for a sanctuary-monograph – is the book of Innes Siemers-Klenner on Güglingen.

A useful list of monographs see also here.

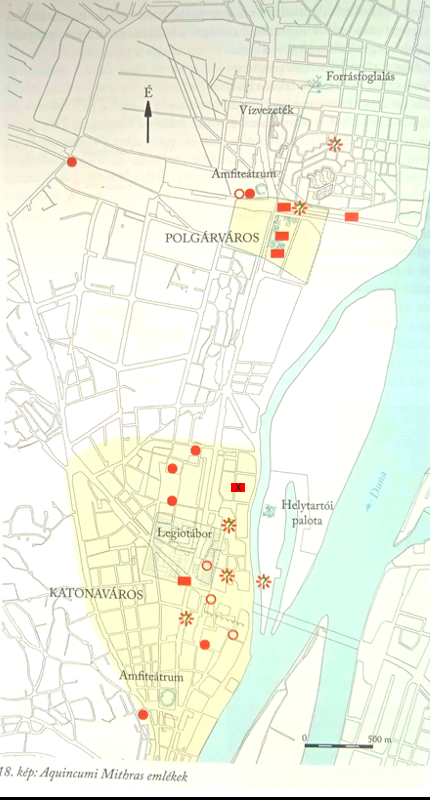

Aquincum was one of the largest urban centres of the Danubian provinces (with Carnuntum and Apulum). The double city (civilian town, military town, legionary fortress and the praetorium consularis) left us hundreds of votive monuments (459 epigraphic and hundreds of figurative) and several, archaeologically attested sanctuaries as well. From the large quantity of the materiality of religon, Mithras represents far the most relevant material evidence of Roman religious communication in Aquincum.

The altar of Tiberius Pontius Pontianus is one of the oldest attested Mithraic monument of Aquincum, already reused in 1809. It is a unique dedication to Mithras Nabarze, a dedication which we found in Sarmizegetusa too. Dedicated by a tribunus laticlavius, it is not impossible, that it comes from the Mithraeum V. The inscriptions found in 1855 and one known already in the 18th century (CIMRM 1773-1775) could also belong to Mithraeum V (house of the tribunus laticlacius).

The first archaeologically attested monuments of Mithras in Aquincum were discovered already in 1887-1888, when the so-called II. Mithraeum was discovered in the civilian town. The sanctuary was associated with M. A. Victorinus. The sanctuary can be visited in situ in the civilian town (Archaeological Museum of Aquincum). In 1895 in the area of the Krempel mill the Mithraeum III of C. I. Victorinus was discovered. The site is destroyed soon after.

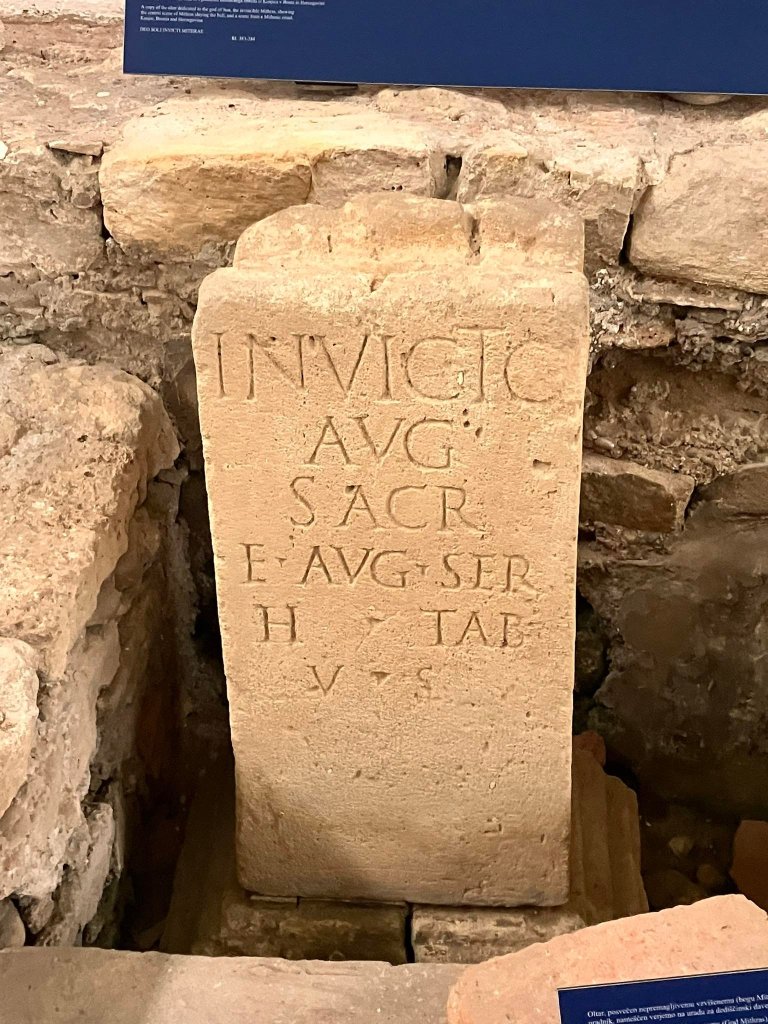

This discovery was followed by another important one before the year of 1908 on Miklós tér, in the NE part of the legionary fort, on the territory of the canabae, where a beautifully carved altar of Mithras was found with another, fragmentary one (Hekler 1908, 285). This discovery might be in relationship with the current, spectacular find (Tit. Aq. I. 261, lupa 6525): Invicto / Mit(h)rae P(ublius) / Ael(ius) ——Atta / act(u)ar(ius) le/g(ionis) II ad(iutricis) p(iae) f(idelis) / Ant(oninianae) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito). The inscription can be dated to the Severan period, the reign of Caracalla. In 1912 in the civilian town another sanctuary was discovered, known as the Mithraeum I, with unique inscriptions dedicated by the Leones to Sol and other representations of Mithras. In 1942-43 the Mithraeum IV (the recently reconstructed Symphorus Mithraeum) was discovered and partially excavated (followed by several, later excavations). Finally, the V. Mithraeum in the house of the tribus laticlavius discovered in 1977 represented one of the last urban mithraea discovered in Hungary (followed by the case study of Savaria in 2011). A relief of Sol and Mithras was discovered in a reused position in 1986 in military context.

The new Mithraeum (named by me as Mithraeum VI) was excavated by Tamás Milbich (excavation leader, Aquincum Museum) and Tibor Budai-Balogh (consultant).

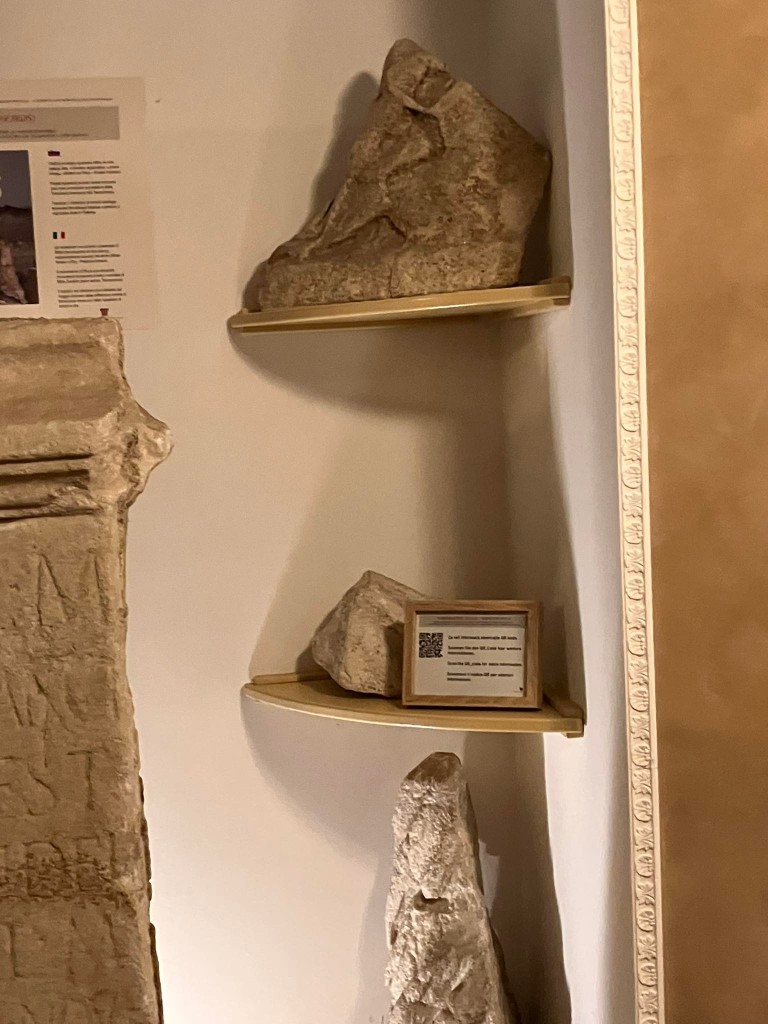

The sanctuary could be related to the already mentioned altar of Publius Aelius —Atta, as their position is extremely close (Miklós tér, Szeszgyár area). The discovery was announced in December 2023, although the area was excavated since 2017-2018. The old factory of Szeszgyár will be transformed into a new and rather monumental building complex. Large parts of the podia (stone slabs and solid structures preserved) were revealed. The central nave of the sanctuary was well preserved. Several finds were identified, among them a fragment of a painted miniature altar with the inscription dedicated to Tra(n)situs (Dei), a unique lead votive representing probably a standing Mithras and the two dadophores and a fragment of a fresco representing Mithras or one of the torchbearers. The excavations will be continued in the spring of 2024.

Photos from Kovács Olivér.

The Danubian provinces are far from being the most urbanised areas of the Roman Empire, however the region had several urbanised (citified) settlements (small urban centres and larger conurbations too). One of the largest urban centres of the region is the double city of Apulum in Roman Dacia (colonia Aurelia Apulensis, municipium Septimium Apulense, the legionary fortress, the praetorium consularis). The large urban centre existed only 170 years in the period of 106-271 AD (and reused systematically since the 4th century), but left us a large amount of arhaeological sites, epigraphic (772 inscriptions in EDH, 1461 in Clauss-Slaby), figurative monuments and small finds too. Monuments from the ruins of Apulum were looted, reused and later, collected since the Renaissance period and researched systematically since 1888. Several important sanctuaries were excavated in the praetorium consularis and in the territory of the municipium Septimium (mithraea) and colonia Aurelia Apulensis (Liber Pater shrine).

Most of the epigraphic and figurative monuments are related to the religious life of the city, which shows a unique cultural, ethnic and religious diversity. The case of Apulum therefore is an ideal case study to study 1) citification of religion and urban religion in provincial context 2) religious competitivity and market-place theory 3) small group religions in interconnected networks 3) religious glocalisation and local appropriations. A preliminary attempt for such methodological questions was presented in my 2018 monograph, where most of the case studies are from Apulum.

A new project focusing on glocalisation and urban religion in Apulum will focus in details on these aspects of Roman religion in an urban context through the comparative case study of Apulum and Carnuntum.

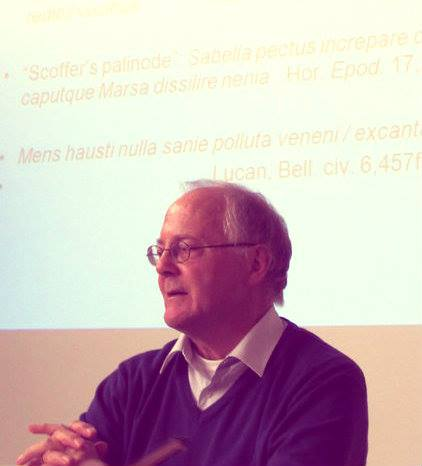

One of the leading scholars of Mithraic studies, Richard Gordon celebrates his 80th birthday in this month. His revolutionary contribution for the study of Mithraism is unquestionable and still inspires dozens of young scholars.

Short presentation of his academic cursus honorum:

1. Higher Education

First degree: Jesus College, Cambridge: 1962-66, Classical Tripos (Ancient History option) Postgraduate: Jesus College, Cambridge: 1966-69; Supervisor: Prof. M.I. Finley. PhD topic: Mithraism in the Roman Empire (unpubl.) (1972)

2. Academic Posts

1969-70: Research Fellow, Downing College, Cambridge 1970-88: Lecturer, then Senior Lecturer in interdisciplinary topics (Ancient Civilisation) in the School of Modern Languages and European History, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK 1979-80: Visiting Fellow, Darwin College, Cambridge 1988- : Private Scholar 2007- : Honorary Professor of Greek and Roman Religion, Erfurt

Major publication in Mithraic Studies:

Gordon 1972

Gordon, R. L., Mithraism and Roman society”, Religion 2 (1972) 92-121.

Gordon 1975

Gordon, R. L., Franz Cumont and the doctrines of Mithraism”, Mithraic Studies , ed. J.R. Hinnells(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1975) 1: 215-48.

Gordon 1976a

Gordon, R. L., The sacred geography of a mithraeum” , Journal of Mithraic Studies 1.2 (1976) 119-65.

Gordon 1976b

Gordon, R. L., A new Mithraic relief from Rome”, JMS 1.2 (1976) 166-186.

Gordon 1976c

Gordon, R. L., A note on the ‘Mithraeum’ at Cyrene”, JMS 1 (1976) 210-221.

Gordon 1978a

Gordon, R. L., Iconographical notes on the Pojejena reliefs”, JMS 2.1 (1977-78) 73-78.

Gordon 1978b

Gordon, R. L., The date and significance of CIMRM 593 [British Museum, Townley Collection]”, JMS 2.1 (1977-78) 148-174.

Gordon-Hinnells 1978

Gordon, R. – Hinnells, J., “Some new photographs of well – known Mithraic reliefs”, JMS 2.1(1977-8) 198-223.

Gordon 1980a

Gordon, R. L., Reality, evocation and boundary in the Mysteries of Mithras”, JMS 3 (1979-80) 19-99.

Gordon 1980b

Gordon, R. L., Panelled complications”, JMS 3 (1979-80) 200-227.

Gordon 1988

Gordon, R. L., Authority, salvation and mystery in the Mysteries of Mithras” ,J.M.C.Toynbee MemorialVolume , eds. J. Huskinson, M. Beard, J. Reynolds (Newnham College, Cambridge, 1988),45-80.

Gordon 1994a

Gordon, R. L., Mystery, metaphor and doctrine in the Mysteries of Mithras” in Studies in Mithraism: Papers associated with the Mithraic Panel organized on the occasion of the XVIthCongress of the International Association for the History of Religions, Rome 1990 , ed. J. 4 R. Hinnells ( Rome: ‘L’Erma’ di Bretschneider, 1994) 103-124.

Gordon 1994b

Gordon, R. L., Who worshipped Mithras?”, Journal of Roman Archaeology 7 (1994), 459-74 (review ofM. Clauss, Cultores Mithrae [1992]), JRA 7 (1994) 459-474.

Gordon 1996

Gordon, L. R, Image and Value in the Graeco-Roman World: Studies in Mithraism and religious art Variorum Collected Studies series (Aldershot, 1996)

Gordon 1998

Gordon, R. L., Viewing Mithraic art: the altar from Burginatium (Kalkar), Germania Inferior,” ARYS 1 (1998) 227-258.

Gordon 2002

Gordon, R. L., Persei sub rupibu s antri’: Überlegungen zur Entstehung der Mithrasmysterien,” in: Ptujim römischen Reich/Mithraskult und seine Zeit: Akten des intern. Symposion Ptuj, 11-15.Okt. 1999 Archaeologia Poetovionensis 2 (Ptuj, 2001 [2002]) 289-301.

Gordon 2004a

Gordon, R., Small and miniature reproductions of the Mithraic icon: reliefs, pottery, ornaments and gems, in M. Martens and G. De Boe (eds.), Roman mithraism: the evidence of the small finds. Papers of the international conference, Tienen, 7-8 November 2001, Amsterdam 2004, 259–283.

Gordon 2004b

Gordon, R. L., Interpreting Mithras in the late Renaissance, 1: the ‘monument of Ottaviano Zeno’ (V.335) in Antonio Lafreri’s Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (1564),” in Electronic Journal of Mithraic Studies 4 (2004) (illustrated).

Gordon 2004c

Gordon, R. L., Traj ets de Mithra en Syrie romaine ” , Topoi (Lyon: Maison de l’Orient) 11.1 (2001 [2004]) 77-136.

Gordon 2005

Gordon, R. L., Ritual and hierarc hy in the Mysteries of Mithras ” , in: Divinas dependencias, 2 in: ARYS4 (2001 [2005]) 245-74. Reprinted in J.A. North and S.R.F. Price (eds.), The Religious History of the Roman Empire: Pagans, Jews and Christians (Oxford 2011) [= Oxford Readings in Classical Studies] 325-365.

Gordon 2006

Gordon, R. L., Mithras Helios astrobrontodaimôn? The re -discovery of IG XIV 998 = IGVR 125 in South Africa,” Epigraphica 68 (2006) 155-94.

Gordon-Alvar 2006

with J. Alvar and C. Rodríguez Cao, “The mithraeum at Lugo ( Lucus Augusti ) and itsconnection with Legio VII Gemina ” , JRA 19.1 (2006) 266-77.

Gordon 2007

Gordon, R. L., Institutionalised religious options: Mithraism. In: Rüpke, J. (ed.), The Companion of Roman Religion, Blackwell-Wiley, 2007, 392‐405.

Gordon 2009a

L.R. Gordon, The Roman Army and the Cult of Mithras: a critical view, in Y. Le Bohec and Ch. Wolff (eds.), L’armée romaine et la religion, Paris 2009, 379–450.

Gordon 2009b

Gordon, R. L., The Mithraic b ody: the example of the Capua Mithraeum,” in: G. Casadio & P.A. Johnston (eds.), Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia , Symposium Cumanum, June 19-22, 2002(Austin: Texas U.P., 2009) 290-313.

Gordon 2012

Gordon, R. L., Mithras” , Reallexikon für Antike u. Christentum vol.24/Lfg. 193 (2012) cols. 964-1009.

Gordon 2013a

Gordon, R. L., On Typologies and History: ‘Orphic Themes’ in Mithraism”, in G. Sfameni Gasparro, A. Cosentino and M. Monaca (eds.), Religion in the History of European Culture. Proceedings of the Ninth EASR Conference and IAHR Special Conference, 14 – 17 Sept.2009, Messina . Biblioteca dell’Officina di Studi Medievali 16 (Palermo 2013) vol. 2, 1023-1048.

Gordon 2013b

Gordon, R. L., The Miles -frame in the Mitreo di Felicis simo and the practicalities of sacrifice” (Comment on A. Chalupa and T. Glomb …. ), Religio: Revue pro Religionistiku 21.1(2013) 33-38.

Gordon 2015a

Gordon, R. L., From Miθra to Roman Mithras”: Appendix to M. L. West, “Ancient Greece” in M. Stausberg and Y. Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina (eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism (Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015) 451- 456.

Gordon 2015b

Gordon, R. L., Entries “Cautes &Cautopates” and “Mithraeum” in Eric Orlin (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions (New York & London 2015) 171 and 603f.

Gordon 2016

Gordon, R. L., Den Jungstier auf den goldenen Schulter zu tragen . Mythos, Ritual und Jenseitsvorstellungen im Mithraskult”, in K. Waldner, W. Spickermann, R.L. Gordon (eds.), Burial Rituals, Ideas of Afterlife, and the Individual in the Hellenistic World and the Roman Empire . Potsdamer Altertumswissenschaftliche Beiträge 57 (Stuttgart 2016) 219- 253.

Gordon 2017a

R. Gordon, Persae in spelaeis solem colunt: Mithra(s) between Persia and Rome. In: R. Strootmann and M.J. Versluys (eds.), Persianism in Antiquity, Stuttgart 2017, 289–327.

Gordon 2017b

Gordon, R. L., Nature, order and well -being in the Roman cult of Mithras”, in A. Hintze and A. Williams (eds.), Holy Wealth: Accounting for this World and the Next in Religious Beliefand Practice: Festschrift for John R. Hinnells . Iranica 24 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2017), 93-130.

Gordon 2017c

Gordon, R. L., From East to West: Staging religious experience in the Mithraic t emple”, in S. Nagel, J. -F. Quack and C. Witschel (eds.), Entangled Worlds: Religious Confluences between Eastand West in the Roman Empire. The Cults of Isis, Mithras and Jupiter Dolichenus. Proceedings of the Colloquium held at Heidelberg 26-29 Nov. 2009. OrientalischeReligionen in der Antike 22 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017) 413-442.

Gordon 2017d

Gordon, R. L., Projects, performance and charisma: Managing small religious groups in the RomanEmpire”, in R.L. Gordon, G. Petridou, and J. Rüpke (ed s.), Beyond Duty: Religious Entrepreneurs and Innovators in the Imperial Era . RGVV 66 (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2017) 275-313.

Gordon 2019a

R. Gordon, The cult of Mithras in Late Antiquity. Review of Walsh, David: The cult of Mithras in Late Antiquity development, decline and demise ca. A.D. 270-430, Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2018, in ARYS Antigüedad Religiones y Sociedades 17 (2019), 461–475.

Gordon 2019b

Gordon, R. L., Staging Mithras: Mystagogues and meanings’, Politica Antica 89 (2019) 141-170.

Gordon -Martens-Ervynck 2020

with Marleen Martens and Anton Ervynck, “ The Reconstruction of a Banquet and Ritual practice at the mithraeum of Tienen (Belgium): New Data and Interpretations ” , in M.M.McCarty and M. Egri (eds.). The Archaeology of Mithraism . BABesch Supplementaryseries (Leuven: Peeters, 2020) 11-22

Gordon 2021a

R. Gordon, A brief history of Mithraic studies, in L. Bricault, R. Veymiers and N. Amoroso (eds.), The Mystery of Mithras: Exploring the Heart of a Roman Cult / Le Mystère Mithra. Plongée au cœur d’un culte romain, Morlanwelz 2021, 51–61.

Gordon 2021b

Gordon, R. L., with Andreas Hensen. ‘Das Mannheimer Mithras -Relief: Studien zu seiner Herkunft und Ikonographie’, in J. Lipps, S. Ardeleanu, J. Osnabrügge, C. Witschel (eds.), Die römischenSteindenkmäler in den Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, Mannheim . MannheimerGeschichtsblätter, Sonderveröffentlichung 14 (Mannheim 2021) 173-189 (184-189);eidem: Kat. Nr. 88-89, 465-471 (467-471): Entry on CIMRM 397.

When I began to work on Roman Mithras, there were four people alive from the grand generation of scholars who revolutionized the study of Roman religion and Mithras in the 1970s, creating the third big wave of Mithraic studies after Cumont and Vermaseren: Robert Turcan, John Hinnells, Richard Gordon, and Roger Beck. Today only one of them is with us (R. Gordon).

I am really sad to read that Roger Beck passed away in April this year. His studies and paradigmatic book from 2006 will be and remain a star on the great mantle of Mithras. I was so happy when he answered my message a few years ago. Have a great journey in the Light, Pater.

One of my first letters for an international “celebrity” in academia was addressed for Roger Beck. His answer was a great support for the young researcher in 2010:

S T T L

Roger Beck (1937-2023) professor emeritus of classics in the Department of Historical Studies and former acting principal of the Mississauga campus at the University of Toronto, Canada.Born in England, Roger Beck received his BA from Oxford University. He obtained his PhD in Classical Philology from the University of Illinois in 1971. As Professor Emeritus in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Toronto Mississauga, Beck held several administrative positions, including Acting Principal (1991-2), Associate Dean (1985-91), Vice-Principal Academic (1986-91), Chair of Erindale College Council, and Chair of the Academic Board of the Governing Council of the University. Beck was a world authority on ancient religion, particularly the cult of Mithras, publishing prolifically on the topic. He contributed significantly to the development of UTM’s department of Theatre and Drama Studies. Also a playwright, Beck’s original works and translation were presented at UTM’s Studio Theatre and the Toronto Fringe Festival. Obituary here. and here.

Major works of Roger Beck on Roman Mithras:

Beck 1976a

Beck 1976b

R. Beck, A note on the scorpion in the tauroctony, Journal of Mithraic Studies, 1976

Beck 1976c

Beck, R., Interpreting the Ponza zodiac, I’, JMS 1: 1–19. (1⁄4 Beck 2004c: ch. 9, pp. 151–69).

Beck 1977

Beck, R., Cautes and Cautopates: some astronomical considerations’, JMS 2: 1–17.

Beck 1979

Beck, R., Sette Sfere, Sette Porte, and the spring equinoxes of A.D. 172 and 173’, in Biachi 1979: 515–29.

Beck 1980

R. Beck, Interpreting the Ponza Zodiac II, Journal of Mithraic Studies, 1980

Beck 1982

Beck, R., The Mithraic torchbearers and ‘‘absence of opposition’’ ’, Classical Views, 26, ns 1: 126–40.

Beck 1985

Beck, R., Four Dacian Tauroctonie: affinities within a group of Mithraic reliefs. In: Apulum 22, 1985, 45-51.

Beck 1987

R. Beck, Merkelbach’s Mithras, Phoenix 41, 1987, 196-316.

Beck 1988

Beck, R., Planetary gods and planetary orders in the mysteries of Mithras, Brill, Leiden, 1988

Beck 1994

Beck, R., ‘In the place of the Lion: Mithras in the tauroctony’, in Hinnells 1994, 29–50 (Beck 2004c: ch. 13, pp. 267–91).

Beck 1998a

Beck, R. The mysteries of Mithras: a new account of their Genesis. Journal of Roman Studies 88, 1998, 115-128.

Beck 1998b

Beck 2000

Beck 2001

Beck, R., History into fiction: the metamorphoses of the Mithras myths, Ancient Narrative 1, 2001, 283-300

Beck 2003

Beck, R., New thoughts on the genesis of the Mysteries of Mithras’, Topoi, 11, no. 1: 59–76.

Beck 2004a

R. Beck, Beck on Mithraism: collected works and new essays, Routledge, London, 2004

Beck 2004b

Beck, R., Mithraism after “Mithraism after Franz Cumont” 1984-2003. In: Beck 2004, 3-31.

Beck 2006

R. Beck, The religion of the Mithras cult in the Roman Empire: mysteries of the unconquered sun, Oxford–New York 2006.

Beck 2013

Beck 2014

Beck 2015a

Beck 2015b

Beck, R., Sacred Caves. In: Oxford Classical Dictionary Online, 2015.

In 2008 I was hesitating on my future, as a student: what should I study, what are the most interesting parts of history, I would like to reseach? Numerous professors were trying to push me to Hungarian history, especially Renaissance history, but my devotion towards antiquity and Roman archaeology and religion was already established. I was interested also in the reception of antiquity, this field remained also among my favourites, but an accidental archaeological excavation in Porolissum changed my mind: a German team promissed us, that we will excavate in Porolissum (Dacia, Romania today) a mithraeum inside the Roman auxiliary fort. This would have been a highly unusual, exceptional case and as I was already suspicious in this issue (it turned out to be a cisternium), I read all I could on Roman Mithras in 2009-2010 and wrote my BA thesis on the cult of Mithras in Sarmizegetusa, contextualising the material in a broader historical and religious context of the province and beyond. I used the first time in this period in Romania the books of Jörg Rüpke, who will become my PhD supervisor few years later: a dream I could never even imagine in 2009.

My BA thesis on Mithras in Sarmizegetusa is still unpublished. My first article ever published was also on Roman Mithras in 2010 followed by several others since.

Here are my book chapters, studies and reviews on Roman Mithras published in the period of 2010-2023.

- Dacia and the Cult of Mithras. In: Mithras Reader: Journal of Greek, Roman and Persian Studies, Vol III., London, 2010, 84-99.

- Mithras – un zeu antic si modern. In: Trifescu, Valentin (ed.), Confulente si particularitati europene. Cluj, 2010, 137–146. [Mithras: an ancient and modern divinity]

- Searching for the lightbearer: notes on a Mithraic relief from Dragu. In: Marisia, XXXII, 2012, 135–145.

- Cultul lui Mithras: itinerarul zeului misterelor. In De Antiquitate 4, 2012, 54-77.

- Micro-regional Manifestation of a Private Cult. The Mithraic Community in Apulum. In: Moga, Iulian (ed.), Angels, demons and representations of Afterlife within the Jewish, Pagan and Christian Imagery. Antiqua et Mediaevalia. Iasi, 2012, 43 – 73.

- Comunitatea mithraica din Apulum: manifestari ale cultului. In: Petan, Aurora – Batranoiu, Raluca (ed.), Arheologie si Studii Clasice vol. II., Dacica 2012, 125 – 156.

- The Mithraic statue of Secundinus from Apulum. In: ReDiva I., 2013, 45 – 65.

- Monumente sculpturale mithraice din Apulum, De Antiquitate 6, 2013, 32-46.

- Pantheon journal. Nr.7/1. In: Ephemeris Napocensis XXIII. 2013, 369-371.

- Notes on the Mithraic small finds from Sarmizegetusa. In: Ziridava, 28, 2014, 135-148.

- Mithras rediscovered. Notes on the CIMRM 1938 (with George Bounegru, Victor Sava). In: Ziridava 28, 2014, 149-156.

- Sicoe, Gabriel, Mithräischen Steindenkmäler aus Dakien. In: Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2014. 10. 56.

- A nemzetközi Mithras kutatás legújabb eredményei. Ókor folyóirat XIII. évfolyam, 4. szám. (2014), 54 – 60.

- Mithras rediscovered II. Further notes on CIMRM 1938 and 1986. In: JAHA 2, 2015, 67-73.

- Notes on a new Cautes statue from Apulum. In: Archaeologisches Korrespondenzblatt 2/2015, 237-247.

- The cult of Mithras in Apulum: communities and individuals. In: Zerbini, Livio (ed.), Culti e religiositá nelle province danubiane”, 2015, 407-422.

- Notes on a new Mithraic inscription from Dacia. (with I. Boda & C. Timoc). In: Mensa Rotunda Epigraphica, Cluj Napoca, 2016, 91-104.

- Mithras kultusza Daciában. Művelődés 70, 2017, 26-29.

- The material evidence of the Roman cult of Mithras in Dacia. CIMRM Supplementum of the province, Acta Antiqua, 58, nr. 1-2, 2018, 325-357.

- Csaba Szabó, Sanctuaries in Roman Dacia: materiality and religious experience, Archaeopress, Oxford, Roman Archaeology Series 49, 2018, 98-120.

- Reinterpreting Mithras. A very different account, Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 69, 2018, 211-216.

- Understanding Roman Mithras. Notes on Three New Books. Review of Adrych, Philippa, Bracey, Robert, Dalglish, Dominic, Lenk, Stefanie & Wood, Rachel (2017), Images of Mithra; Mastrocinque, Attilio (2017), The Mysteries of Mithras; and Panagiotidou Olympia & Beck, Roger (2017), The Roman Mithras cult, ARYS 16, 2018, 469-479.

- Sacralised spaces of Mithras in Roman Dacia. Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 72,1, 2021, 55-65.

- Mithras in Apulum. Between local and universal. In: L. Bricault, R. Veymiers & N. Amoroso (éd.), The Mystery of Mithras: Exploring the Heart of a Roman Cult / Le Mystère Mithra. Plongée au cœur d’un culte romain, Musée royal de Mariemont, Morlanwelz, 2021, 343-349.

- Archaeology of a mithraeum: the case of Caesarea Maritima. Cercetări Arheologice 28/1, 2021, 325-330.

- The reception of Roman Mithras in Transylvania in the 18 th -19 th century, La Revista de Historiografía (RevHisto), 37, 2022, 249-271.

- Review: Bricault (L.), Roy (P.) Les cultes de Mithra dans l’Empire romain. 550 documents présentés, traduits et commentés. Pp. 636, 272 black and white photos, plans and maps. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Midi, 2021, Classical Review, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009840X2200107X

- Csaba Szabó, Roman Religion in the Danubian Provinces: Space Sacralisation and Religious Communication during the Principate (1st–3rd century AD), Oxford, Oxbow Books, 2022, 176-182.

- Csaba Szabó, Miruna Libiță-Partică, Ioan Muntean, Mithras exhibited. Perspectives of sensory museology in Mithraic contexts, Cercetări Arheologice, Vol. 30.2, pag. 737-762, 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.46535/ca.30.2.19

The cult of Roman Mithras attracted the attention of the academic scholarship and the greater public since the 19th century (and in the antiquarian traditions, even before, since the Renaissance). In the last few decades, the scholarship produced an incredible number of monographs and studies, there is almost every year a new book on Roman Mithras. Some might interpret this as a “renaissance” of the Mithraic Studies, however we prefer to say that finally, Mithraic Studies – which separated this cult from its own cultural, historical and polytheistic context – actually have changed and finally, interprets the Roman cult of Mithras in its own historical context, within the complex religious market of the Roman Empire (Rüpke 2018 – a short chapter on Roman Mithras, or Woolf 2019 where Mithras is one of the many global and mobile divinities of the empire scale network of religion).

One of the main issues of this research area is the materiality of the cult: with almost 120 sanctuaries excavated and thousands of epigraphic, figurative monuments and small finds in dozens of countries in Europe, Nothern-Africa and the Near East (and even in private collections in the New World), a new digital and interactive CIMRM Supplementum would be essential now. While the local studies and theoretical approaches are also important, collecting the material would be even more important. Exhibitions focusing on the cult aimed to produce important catalogues, which can serve as CIMRM Supplement, although none of these can be comprehensive and complete. Important exhibitions were organised in the last years, like the one in the Landesmuseum Karlsruhe in 2013, however that was focusing on several cults. Recently, an international project and collaboration between three major European museums produced the largest ever Mithras-exhibition, an itinerary project between Mariemont, Toulouse and Frankfurt (2021-2023). The catalogue of the itinerary exhibition was published in French and English and it is one of the best synthesis on the cult of Mithras with several new case studies and high quality photos of old and new finds as well.

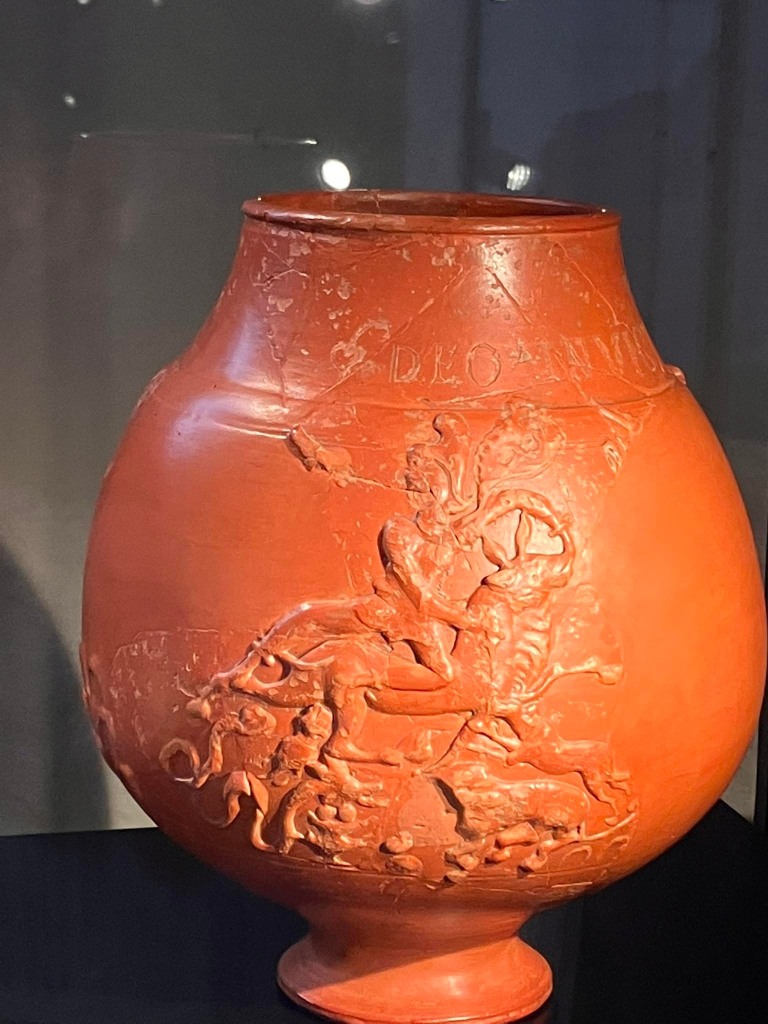

Each of the exhibitions had a slightly different material and museological approach, influenced also by the local possibilities. The Mariemont exhibition was opened during the pandemic, therefore they invested a lot in the digital promotion of the event. In 12-13th March 2023 I had the chance to visit the exhibition in the Archaeological Museum of Frankfurt. The exhibition was focused around the amazing local finds from Nida-Heddernheim (today in the North-Western part of Frankfurt, in the area of the Rosa Luxemburg street and south of the Nordwestcentrum, Römerstadtschule). The Roman vicus of the fort had at least four, archaeologically well attested sanctauries of Mithras (a fifth is presumed) discovered in the 19th century (the earliest 200 years ago, in 1823). The finds are not presented in a comprehensive, catalogue-like manner, but there are several posters which explains the history of the discoveries, the context, the history of Nida-Heddernheim and the major finds of the 4 mithraea. Absurdly, there is no map with the modern Frankfurt, therefore the visitor will need to use the google map to find out where is Nida today (50.153406, 8.631575). The map of Roman Dacia appears incorrectly on one of the maps. A particuarity of these finds is the great presence of other divinities in the sanctuary: Epona, Mercurius, Hercules, which is rarely attested in other cases. The iconographic glocality of the visual narratives of Nida is only shortly presented. The great, two sided relief of Nida is in an unfortunate position in front of the reconstructed “mithraeum”, while the photo of the coloured version of this relief is in another room. The reconstructed mithraeum presents the objects in a dark room, which tries to imitate the feeling of a Mithraic sanctuary (darkness, warm environment), however the podia are too small and perhaps, using a projector, interactive voice and visual museology could make this mithraeum much more authentic. The large space of the museum (the former Carmelite Monastery) would be ideal for projections, videos, interactive solutions to use the walls and empty spaces of the monastery. Such methods we can find in Frankfurt, in the Liebieghaus, where is a temporary exhibition on ancient robots and machines presented in a really nice way which stimulates several senses of the visitor. That is what we call today sensory museology.

The second part of the material is exposed in a different room: there one can observe several interesting objects on the side-scenes of the panelled-reliefs, the amazing album from Virunum (which is indeed, a spectacular and historical find), the Brigetio signum of Mithras, several interesting, unique inscriptions and reliefs. Sadly, the amazing relief from Dieburg was not part of the exhibition, only a copy of it. Presenting the mosaics of the Felicissimus mithraeum from Ostia, the symbols of the miles are presented after the old theory, without mentioning the new approach of A. Chalupa and T. Glomb which was accepted also by R. Gordon recently. The amazing Krater from Mainz was also in the exhibition, however a presentation and contextualisation of the scenes of initiation would have been made this amazing object even more important with an interactive manner of presenting all the visualities of initiation presented amazingly recently by N. Belayche. I was happy to see two monuments from Roman Dacia too. The texts are written almost exclusively in German (which was not a problem for me, but what about foreigners with a poor-German knowledge). The work and life of F. Cumont was mentioned, however M. Vermaseren was not really evoked (he and numerous other big names of the research history would deserve at least some photos there – in Malaga, the archaeological museum and in the Ashmolean Museum there is an amazing way to present the history of discoveries, archaeologist biographies).

In summary: the catalogue of the exhibition is an amazing, great work, which serves as a methodological model for further studies, while we can learn for future exhibitions how to present ancient cults, religions, cognitive, historical, historiographic approaches, local and global case studies as well in an interactive, much more “sexy” manner for the 21st century visitors.

Roman religious studies produced a rich corpus of books also in 2022. I listed 21 new titles, but this is certainly not a complete list (numerous books in France, Italy, Spain are hard to access and I am not able to follow the local scholarships from the West anymore). From the new titles of 2022 there are as usually, two Mithras books by Mastrocinque and Fear, several sanctuary monographs, local case studies on names and divine epithets, macro-regional analysis for the Danubian provinces, methodological approaches by Roubekas and Mackey and cognitive approaches by Eidinow and others.

It seems, that epigraphic material and the names of the gods represent a booming field and the divine agency is back in the focus of the research again.

You can check the detailed list of books on Roman religion in the last 10 years HERE. (the last 10 pages are from 2022).

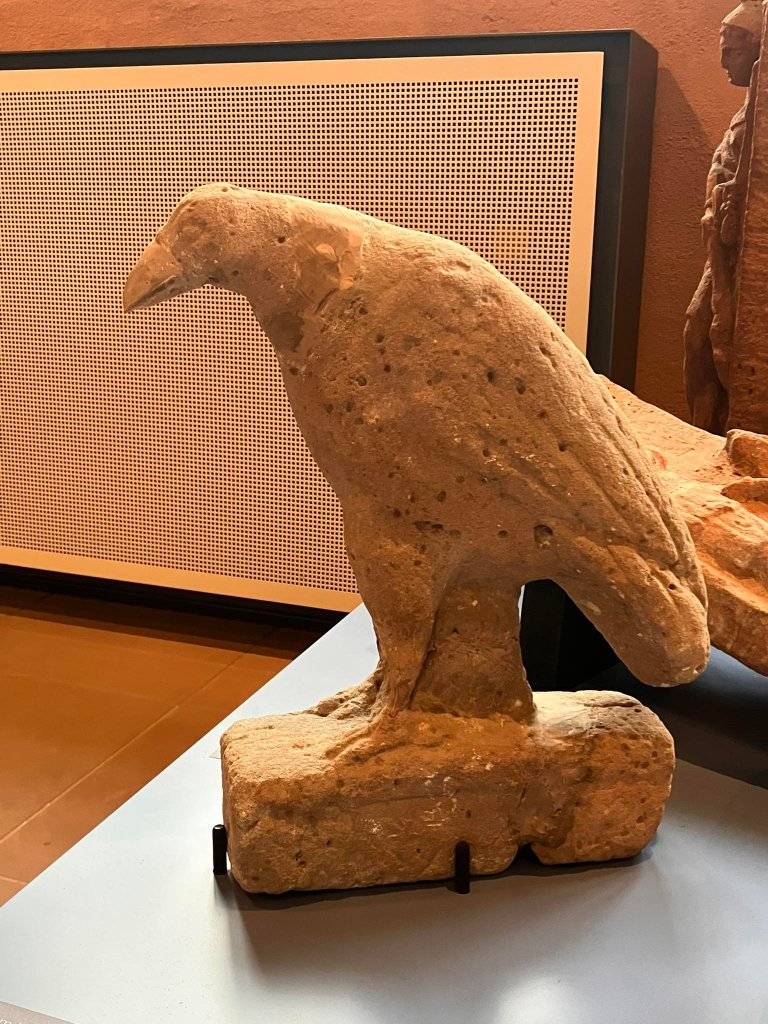

For those who are familiar with the Roman cult of Mithras it is not surprising, that Poetovio, one of the most important Roman settlements of south Pannonia (today in Slovenia) was a central place in the diffusion of the cult in the 2-3rd century AD. The quantity and quality of the Mithraic finds from Poetovio is extraordinary: since 1898 at least 5 mithraea were identified (although the functionality of the building known as mithraeum IV is problematic and the mithraeum V was poorly documented). Vermaseren in the 1950’s in his monumental corpus of Mithraic finds was able to indentify almost 130 Mithraic finds from the 3 known sanctuaries (CIMRM 1487-1618). The material of the so-called mithraeum IV and V were later published in the catalogue of the lapidar in 1988 and in numerous later studies analysed sporadically (see here a summary from 2018 by M. Gojkovici).

The first three mithraea discovered in the end of the 19th and early 20th century is no doubt, served as a mithraeum.

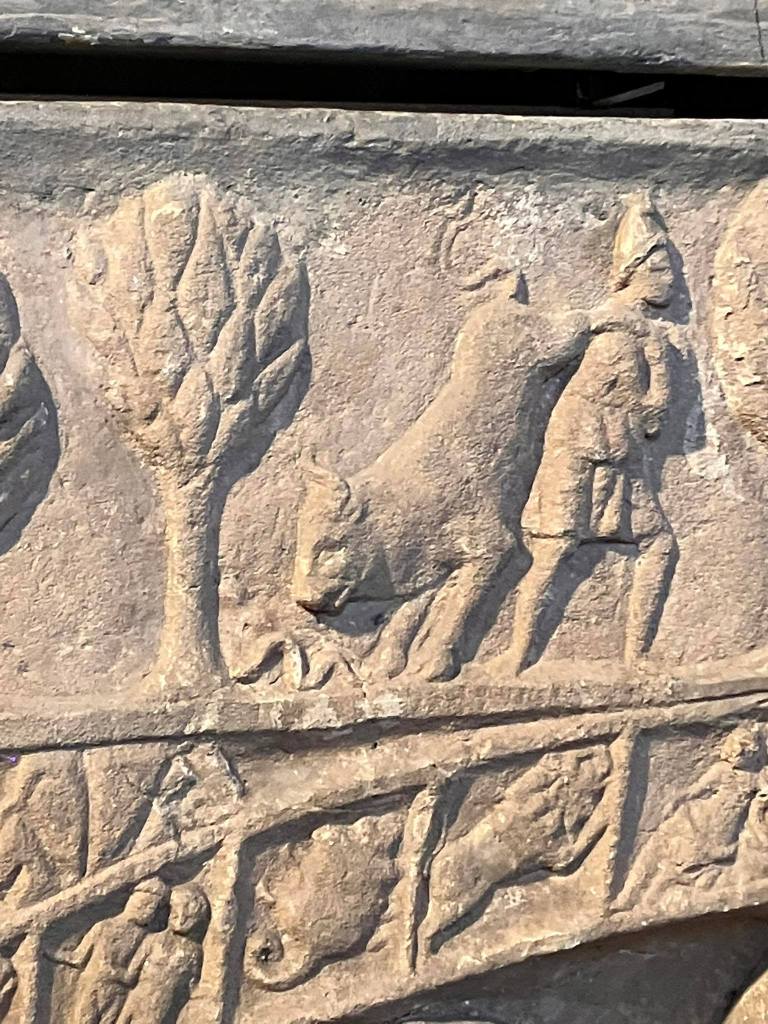

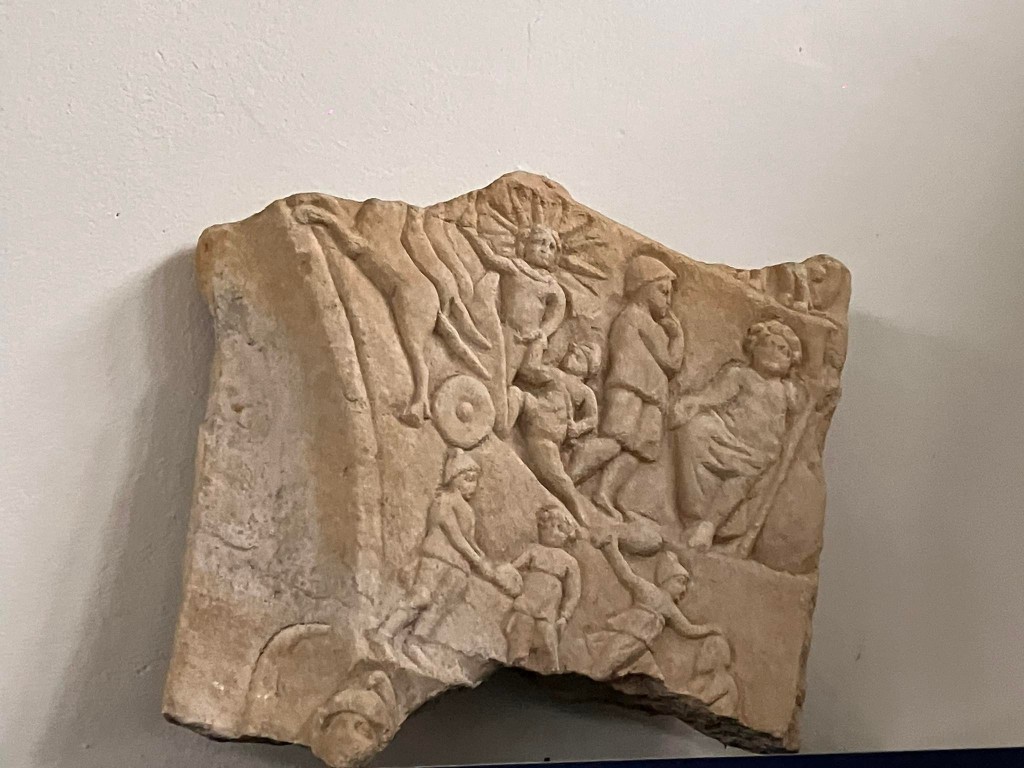

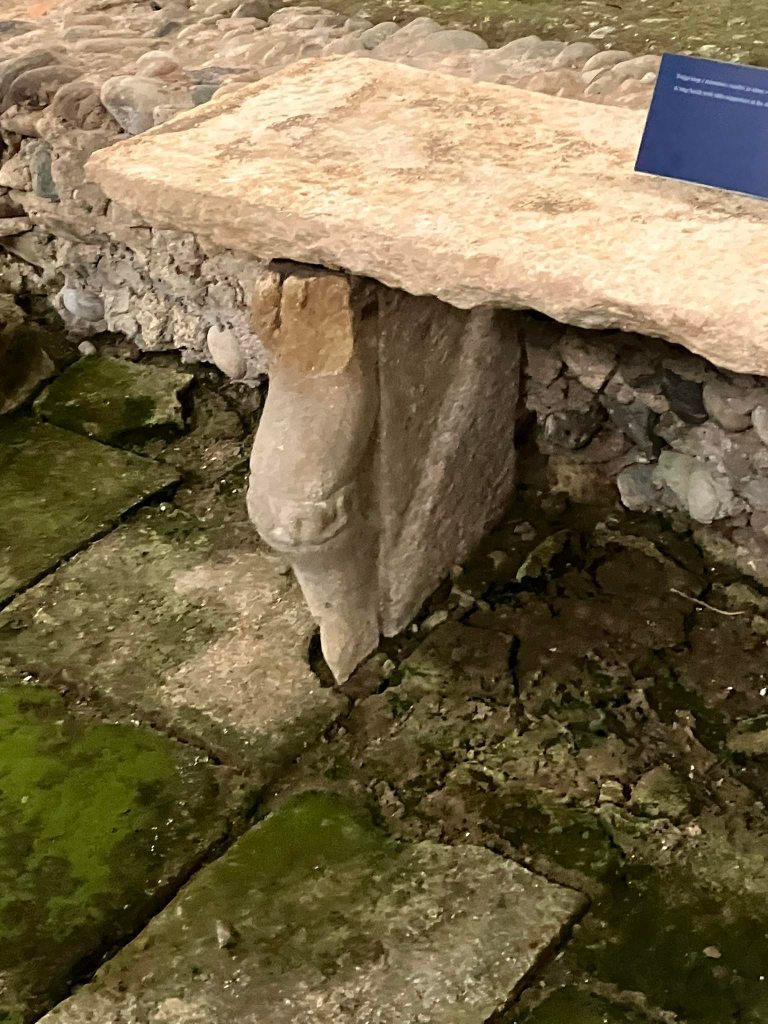

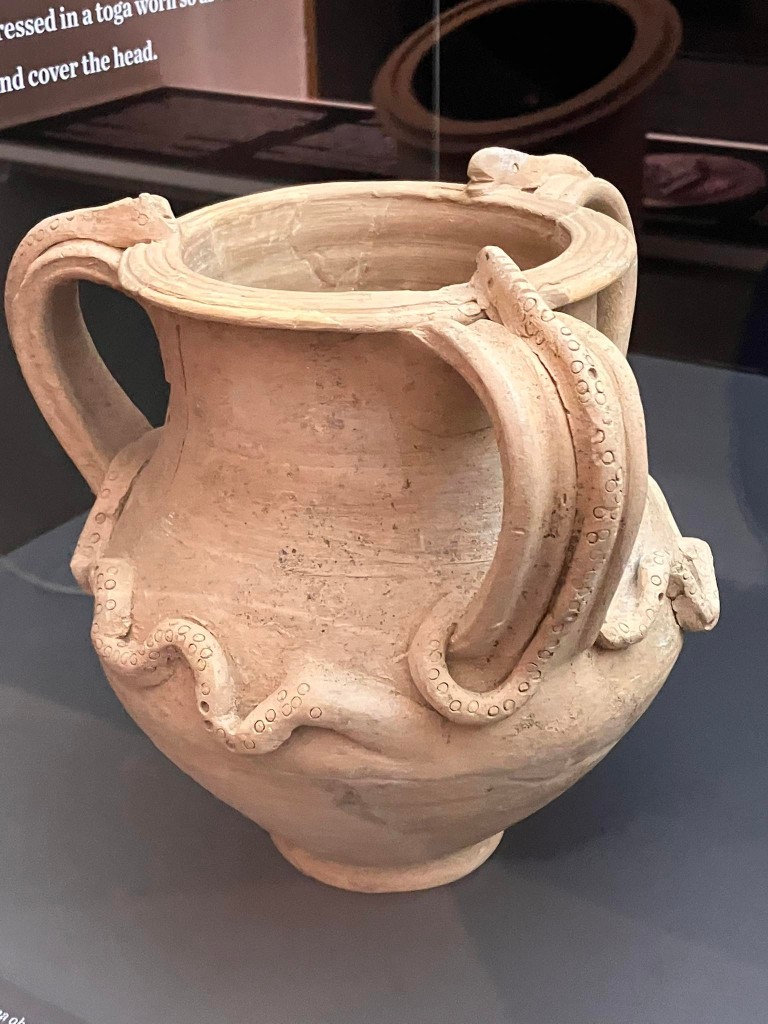

Mithraeum I was founded probably in the early 2nd century by the first generation of Mithras worshippers (if the cult was founded in the Flavian period and expanded in the early Trajanic period between 80 and 100 AD). The first mithraeum – which is much smaller than the third one – has some unique particularities, such as the beautifully decorated altars, a representation of Mithras Taurophoros or two identical texts on two statue bases (representing probably the founder of the first mithraeum). It is closely related to the Publicum Portorii Illyrici as P. Beskow and Tóth István argued already in the 1980’s. Although the altars were found in the mithraeum, their current position (for example Mithras Taurophoros inside the podium) does not reflect their original purpose.

Mithraeum III discovered in 1913 in a villa and domestic building complex area. Vermaseren presumed, that east to the mithraeum there was a temple of Magna Mater, however the functionality of the large building next to the mithraeum was never certainly established by excavation. The mithraeum is monumental, one of the largest mithraeum in the Roman Empire. Built in 2 phases at least, the building has its glory in the late 3rd century, around 260 AD, when vexillations from Potaissa and Apulum, the two legionary centres of Dacia stationed in Poetovio and transformed radically the innner sacred geography of the sacralised space. The altars dedicated almost exclusively by soldiers here reflects the emerging importance of Mithras as a protecting god of the Roman army and imperial power.

Mithraeum V was discovered in 1987 in the area of the Student Dormitory of modern Ptuj. The finds are clearly suggesting the presence of a mithraeum, however the building was poorly documented. A part of the finds are kept in the reception of the Hotel Mitra in Ptuj.

More exeptional photographs you can find on the webpage of Ortolf Harl: HERE. The photographs cannot be published in official academic papers or blogs without mentioning the source. My photos were made during the international conference entitled “Contextualising “Oriental Cults” organised by the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Archaeology of the University of Zagreb, 15-17th September 2022. Photographs with personal portraits cannot be used from this blog without the permission of the author.

Recently the leaders of the European Research Council announced, that the old tradition which obsessively quantified the citations, H-indexes and hierarchyical – often patriarchal – system of academia need a radical change. They published a 20 pages long document where they presents the major changes. This is actually very similar to the so-called Leiden Manifesto.

These are good and welcomed initiatives, which might change hopefully the landscape of academic life, where Central-Eastern Europeans are still marginalised as scholars (financially and in citations too). It is prooved, that “famous scholars” who are dominating the field are authomatically cited and their citation and research indexes are artificially increased.

So based on these old-fashioned academic traditions, it is odd to see the studies of Walter Scheidel focusing on the statistics of citations and quantifying the impact of Anglo-Saxon (American and Brittish) scholars of Roman studies. He published already two studies (here and here) on this issue. A similar list was published by Pilkington. Interestingly, they are focusing only on the impact of American scholars mostly. Scheidel introduced also the impact of Moses Finley and Ronald Syme – the later being one (if not the most) cited historian of Roman Studies (now around 14.000 citations in Google Scholar). His Roman Revolution is cited almost 4000 times. He didn’t analysed the impact of Theodor Mommsen (around 8900 citations), Werner Eck, Géza Alföldy and numerous other scholars from German Altertumwissenschaft. Géza Alföldy for example has at least 6000 citations in Google Scholar, his Social History of Rome is cited 300-400 times in each language (mostly Spanish, German, English). Mary Beard has around 8800 citations, the same as Fergus Millar, Greg Woolf 7300, Jörg Rüpke 7100, Franz Cumont 6000, András Alföldi 4000 and so on.

When it comes to the Romanian scholars of Roman studies, the most cited scholar is Ioan Piso (850 citations). His most popular book is the Fasti I (101 citations). He is followed by Nicolae Gudea (738) – his most cited work is his RGZM chapter on the Limes (79 citations). Dan Dana is cited more than 670 times (his Onomasticum Thracicum more than 100 times), Vasile Parvan is cited almost 500 times, his most popular work is Getica (240 citations for 2 editions). Constantin Daicoviciu is cited 485 times (probably much more in Romanian literature which is not listed in Google Scholar however), his most cited work internationally is his book on ancient Transylvania from 1938 (61 citations). Ioana Oltean is the most cited Romanian woman in Roman studies with more than 450 citations (her synthesis on Dacia is cited 112 times and it is the most cited book on Roman Dacia). Dionisie M. Pippidi is cited 430 times (his Contributii la Istoria Veche a Romaniei is cited 47 times). Vitalie Bârcă has 430 citations (his book on Sarmatians has 57), Sorin Cocis has 402 citations (his book on Roman brooches has 114 citations), Mihai Barbulescu is cited 391 times (his synthesis on history of Romanians is cited 167 times, Interferente spirituale 43 times). Florian Matei-Popescu has 385 citations, his book on Moesia Inferior has 116 citations. Dumitru Protase 354, Doina Benea has 345 citations. Cristian Gazdac is the most cited in Romanian numismatic (318 citations). Eugen S. Teodor has 270 citations, Ovidiu Tentea 262, Lucretiu Mihăilescu-Bîrliba 260, Radu Ardevan 250 (his book on municipal systems of Dacia has 90), Mariana Egri 240, Mihail Macrea 228 (his book on Viata in Dacia romana has 92), Sorin Nemeti 216 (his Sincretismul religios is cited 52 times – the most popular book on Roman religion from Dacia), Alexander Rubel 185, and Emil Condurachi is cited 156 times.

From this list we can see, that the most cited scholars are from the post-war generation, who dominated the Romanian scholarship since the 1970’s (for more than 5 decades) and those senior scholars, who are living abroad (Dan Dana, Ioana Oltean) or well-connected internationally in the last two decades. Epigraphy and military studies (Limesforschung) is still the two strongest fields of the Romanian research, however new approaches (social history, numismatics, religious studies) are also emerging.